Devlog 0 — 20 May 2016

Before the Studio

Back in 2013 I landed what felt like a dream gig: building a VR experience for an indoor attraction park. The brief was ambitious — room-scale virtual reality using a 24-camera markerless motion-tracking system and an Oculus DK1. No controllers, no markers on your body, just you walking through a virtual space while cameras figured out where every limb was in real time.

We spent two years on that project. It was intense, experimental, and constantly on the edge of what the hardware could handle. In the end the attraction park project didn’t survive, but I walked away with something more valuable than any paycheck: a deep, hands-on understanding of what VR could actually do — and more importantly, what it couldn’t do yet.

The Spark

By late 2014 I couldn’t shake an idea. I’d been around music production long enough to know the magic of a real recording console — the tactile feedback of pushing a fader, the satisfaction of dialling in an EQ. What if you could have that experience in VR? Not a flat screen with virtual knobs, but an actual room you could stand in, with a console you could reach out and touch?

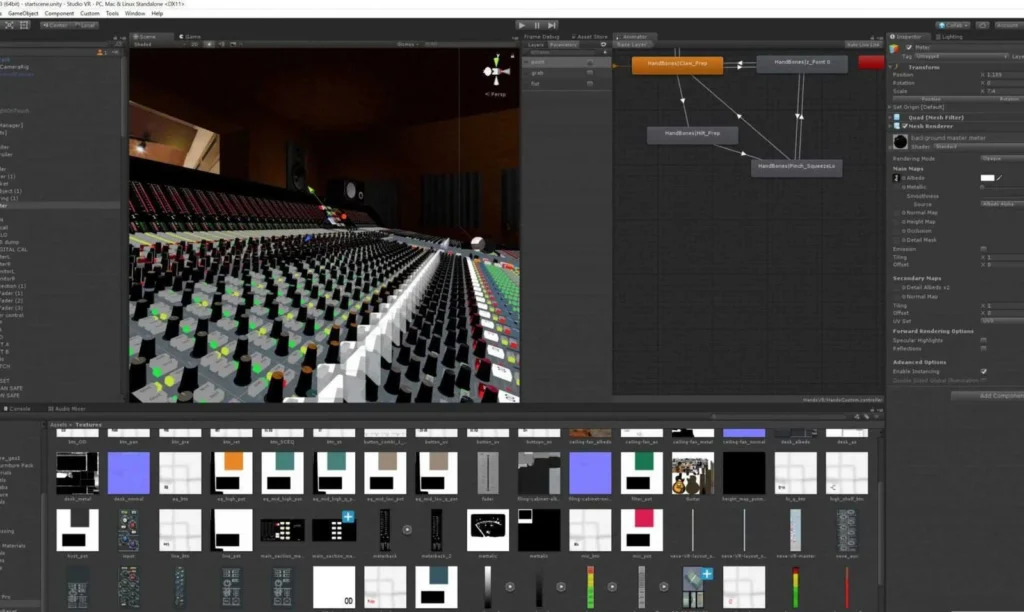

I ran some early tests in Unity. Sliders that responded to your hand. Volume knobs with real throw. An EQ section you could sweep through. It all worked. It felt right. That was the moment I knew this wasn’t just an idea anymore — it was a project.

Choosing the Console

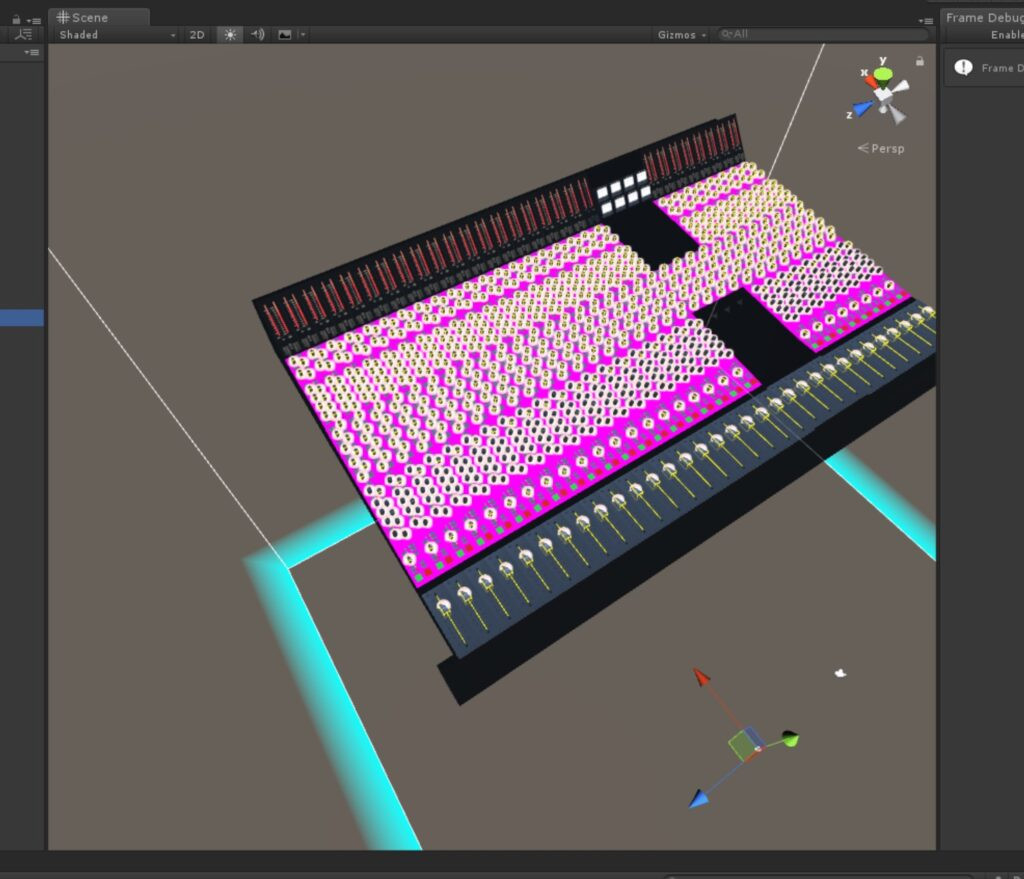

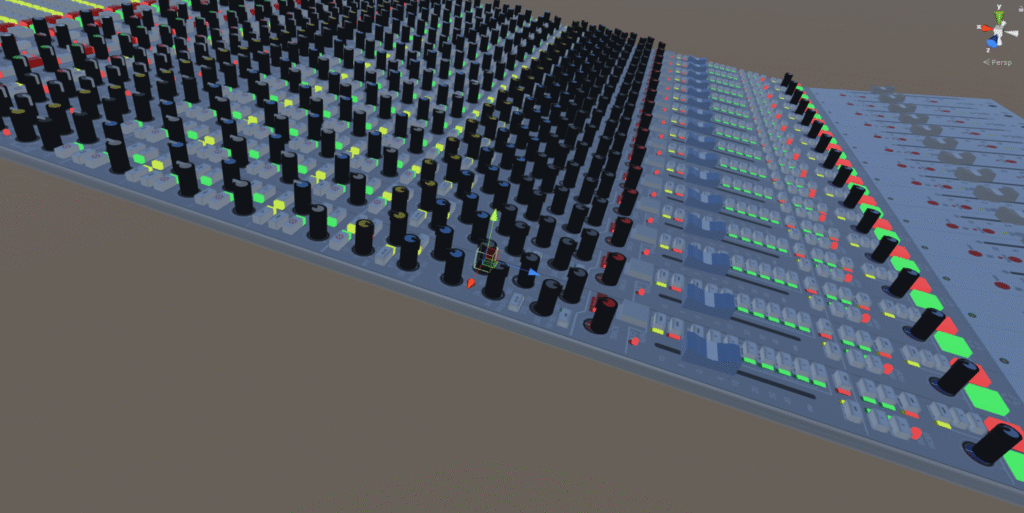

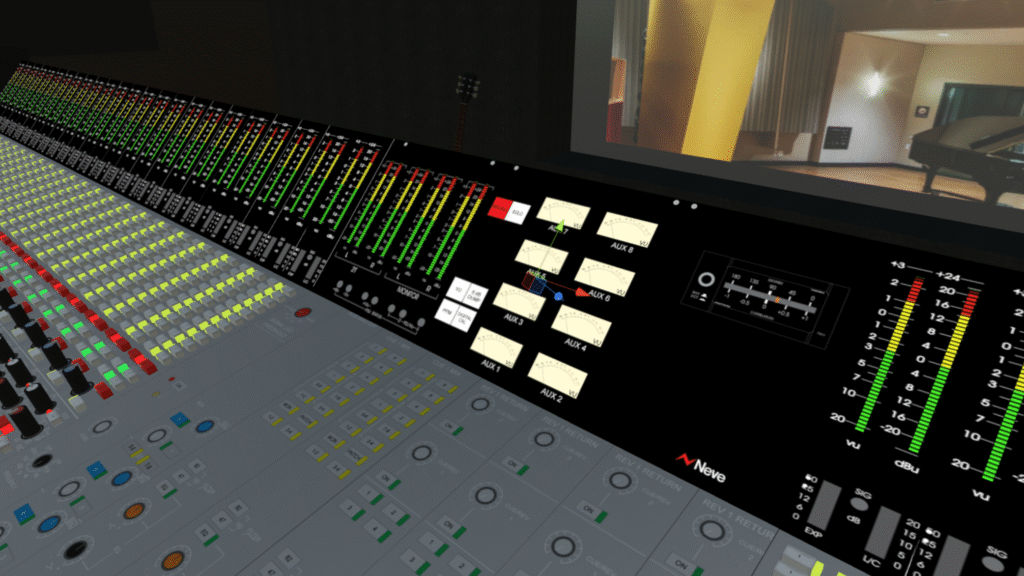

Choosing which console to model was a journey in itself. It started with the Sound City documentary — if you haven’t seen it, Dave Grohl basically made a love letter to the Neve console at Sound City Studios. That sent me down a rabbit hole into Focusrite’s history, which traces back to Rupert Neve himself. And then I landed on the AMS Neve VR Legend.

The VR Legend is a gorgeous piece of engineering — a large-format console with an enormous feature set. But honestly? Part of the reason I chose it was staring me right in the face. The console is literally called the “VR.” It was already in the name. Sometimes the universe just lines things up for you.

Building the Proof of Concept

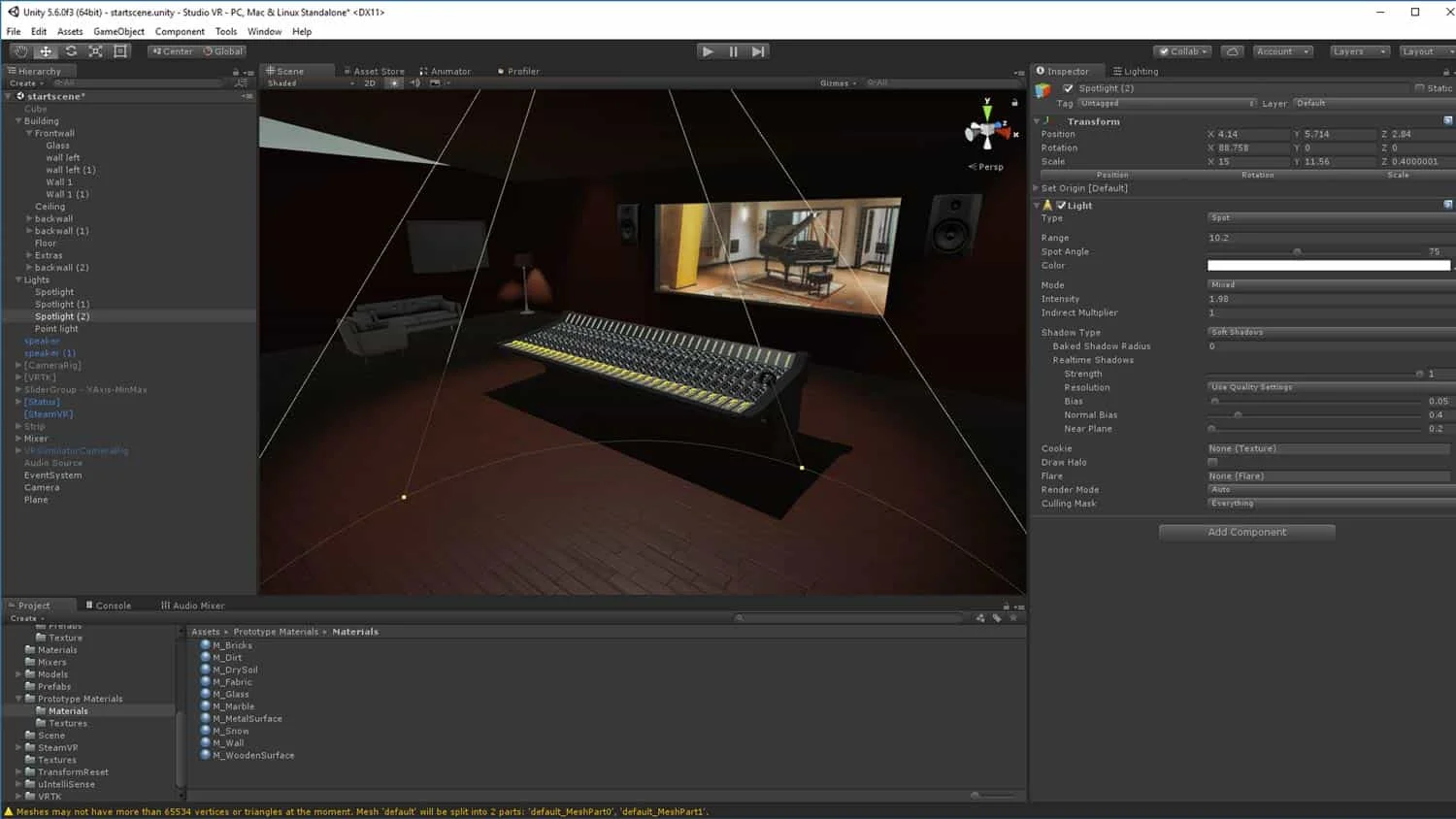

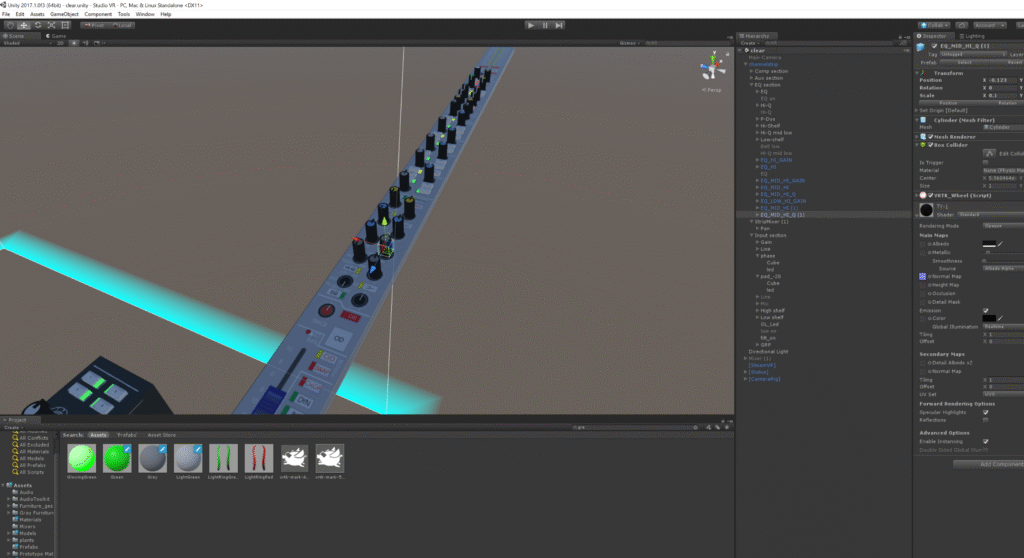

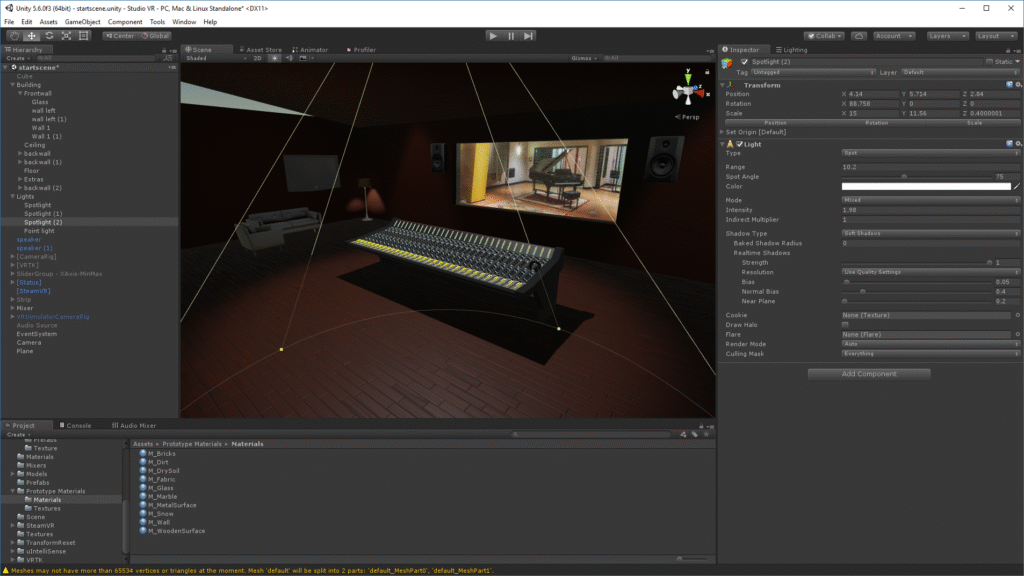

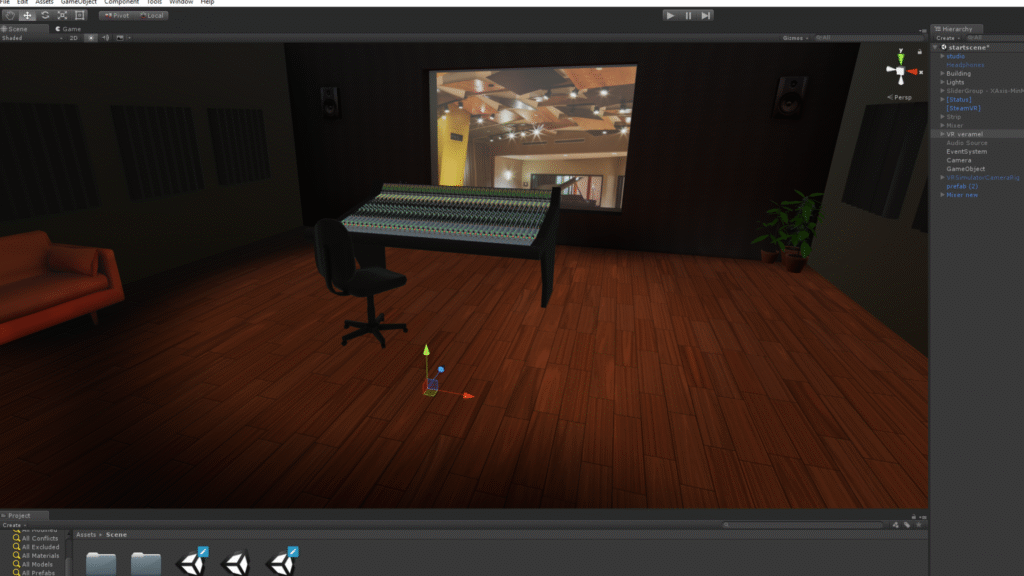

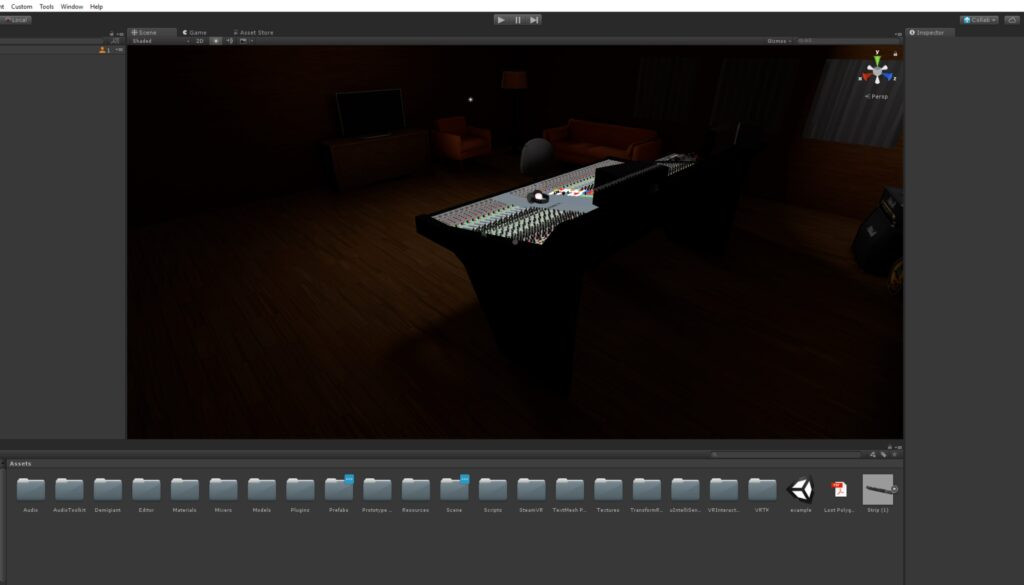

The first proof of concept was basic but functional. I modelled the console with working EQ, level controls, and monitoring. For playback I built a virtual 24-track Studer tape machine that acted as the file player — because if you’re going to dream, you might as well dream in analogue. You could load tracks, solo channels, adjust the mix. It was rough around the edges, but it was real.

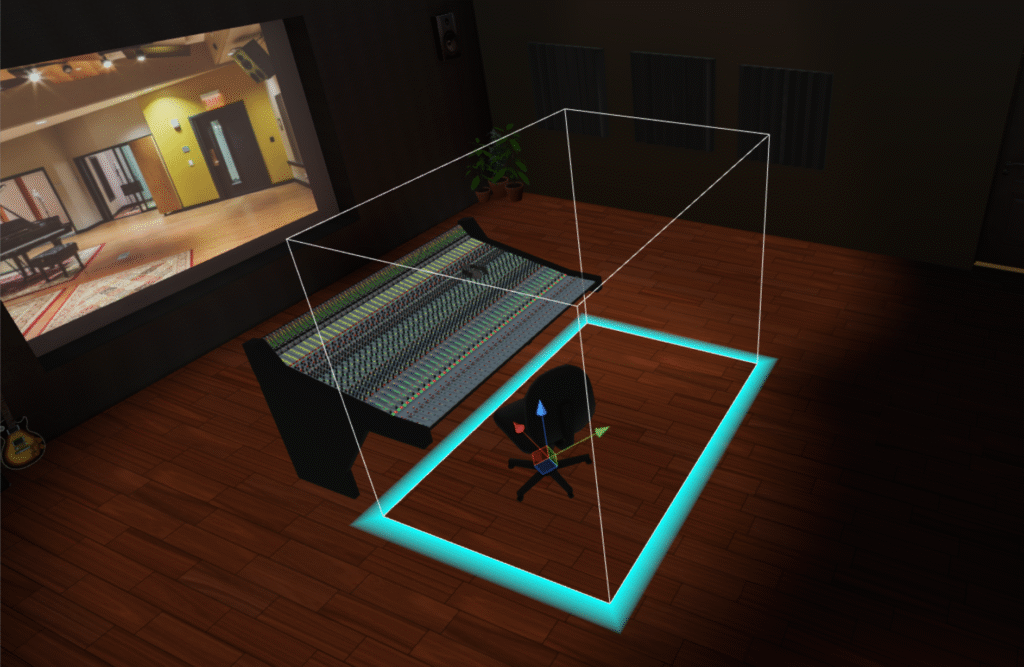

I also built a mock-up control room around the console. VR presence matters more than most people realise. You need walls, a ceiling, acoustic treatment on the surfaces, maybe a window into a live room. Without that environment, you’re just floating in a void with some faders. With it, you’re standing in a studio. That distinction makes all the difference.

The Three Hardest Problems

Pretty quickly I ran into three challenges that would define the entire development process going forward. Every decision I’ve made since traces back to these.

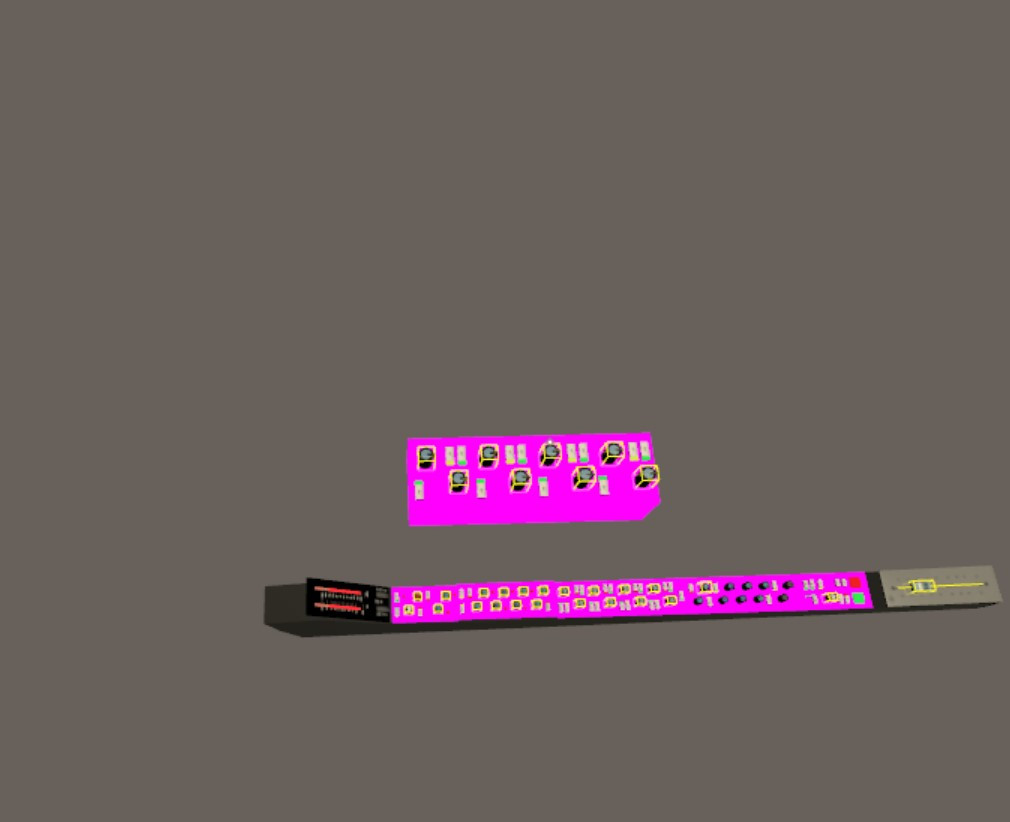

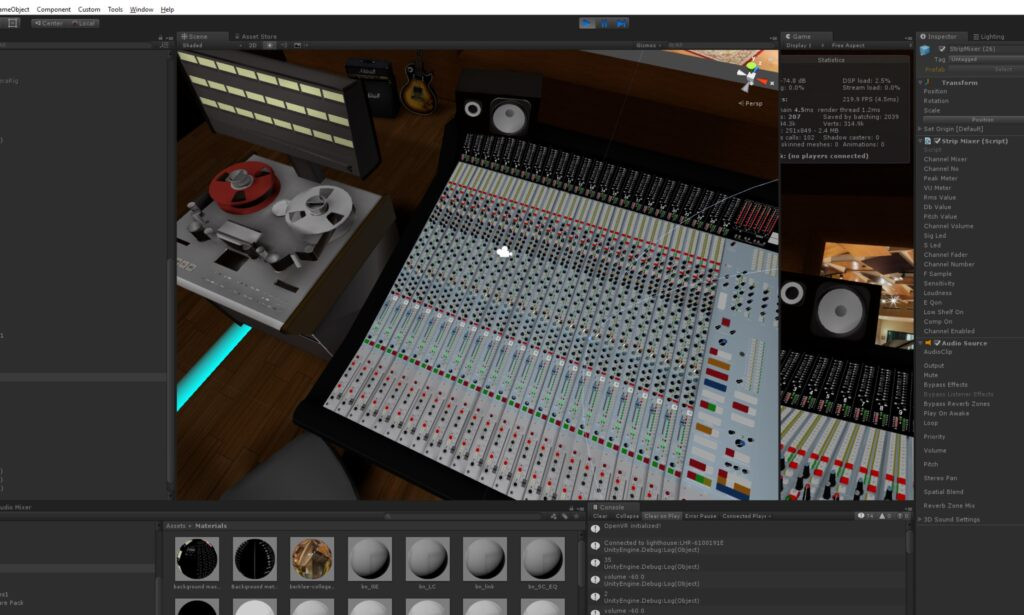

1. Graphics optimisation. VR demands 90 frames per second on two screens simultaneously. A detailed studio environment with a fully modelled console, realistic lighting, and proper textures? That’s a lot of polygons fighting for every millisecond of render time. I had to learn every optimisation trick in the book — and then invent a few more.

2. Audio CPU. Real-time audio processing is expensive. Running EQ, dynamics, and routing across 24+ channels while the graphics engine is already maxing out the hardware? Something had to give. This is what pushed me to learn C++ — I needed to write custom audio plugins that were lean enough to coexist with the visual rendering without either one choking.

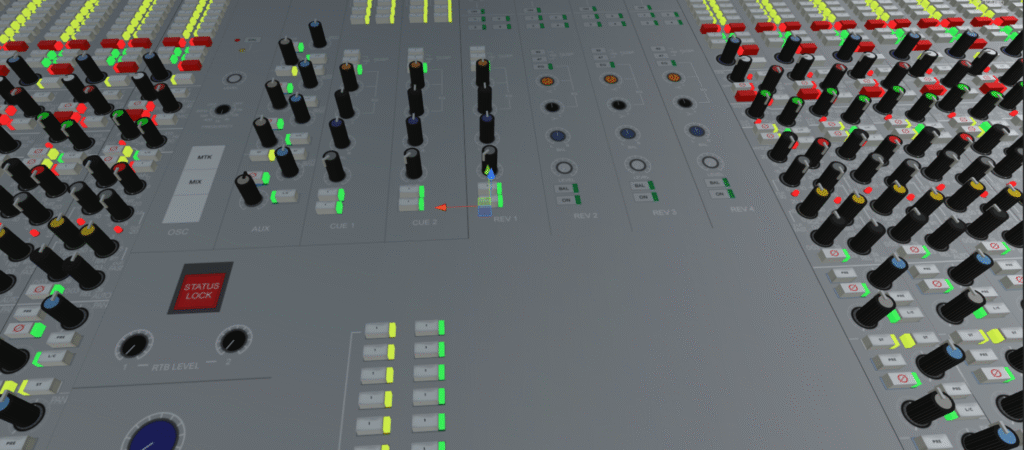

3. The VR interface problem. A real Neve console has hundreds of tiny buttons, switches, and knobs packed together. Your hands in VR aren’t nearly as precise as your real fingers. I had to develop a system combining haptic feedback with visual magnification — essentially zooming in on the section you’re interacting with so those tiny controls become usable without breaking the sense of presence.

A Vision Shared

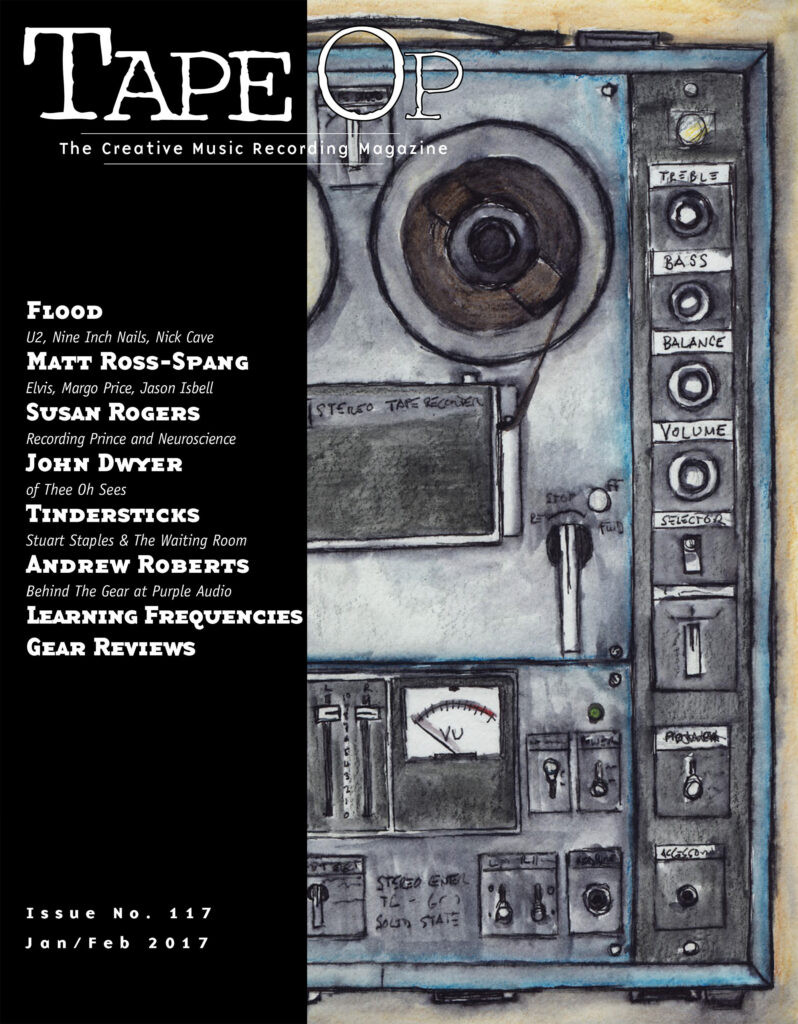

While researching whether anyone else was thinking along the same lines, I stumbled across an article by John La Grou in Tape Op Magazine. La Grou is a respected figure in pro audio — he’s designed analogue circuits, co-founded Millennia Media, and generally spent decades thinking about where audio technology is heading.

His article predicted that by 2050, recording studio environments would exist primarily in virtual reality. Engineers would work with virtual consoles, virtual outboard gear, and virtual rooms — not as a gimmick, but because it would genuinely be a better way to work. The spatial interaction, the tactile feedback through haptics, the ability to customise every aspect of your workspace. He saw it all coming.

“We will work in a virtual control room, surrounded by virtual equipment and virtual co-workers, yet faithfully processing real audio with extraordinary dexterity and uncompromised sonic fidelity. All this might sound far-fetched and futuristic, but the core technologies already exist, and the pace of progress suggests that a full-immersion VR audio workstation is not a question of if, but when.”

— John La Grou, Tape Op Magazine

I reached out to La Grou after reading the article. It was reassuring to know that someone with his experience and credibility was imagining the same future I was actively trying to build. His timeline was 2050. I was hoping to beat that by a few decades.

This was devlog zero — the starting point. Everything that comes after builds on the foundation laid here: the VR experience from the attraction park, the choice of the Neve VR, the proof of concept, and the three challenges that would keep me up at night for years to come. The studio was no longer just an idea. It was underway.