Devlog 8 — May 2023

The Breaking Point

All Unity3D work on the Retro Recording Studio has stopped. The new studio is being built from scratch in Unreal Engine 5.

If you follow indie game development at all, you probably know about the Unity pricing controversy that sent shockwaves through the community. I wasn’t directly affected by the new fee structure, but I understood what it meant — and more importantly, it confirmed something I’d been feeling for years.

Unity stopped being an engine-first company somewhere around 2017 or 2018. Features were announced and never finished — DOTS Audio being the most painful example for my use case. Bugs went unfixed for years. The leadership under John Riccitiello felt disconnected from the people actually building things with the tool. I’d been working in Unity since 2013, and I’d watched it slowly drift away from the developers who made it successful.

The pricing debacle wasn’t the reason I left. It was the permission I needed to stop making excuses and go.

First Contact with Unreal

What actually pulled me toward Unreal was MetaSounds. I’d been reading about it and realized it was everything DOTS Audio should have been — a node-based audio synthesis and processing system built into the engine, designed for real-time use. For a project that’s fundamentally about audio, that mattered more than anything else.

So I opened Unreal Engine 5 and started learning. The first few weeks were rough. Everything was in a different place, the workflows felt alien, and I kept reaching for tools that didn’t exist the way I expected. But here’s the thing that told me I was on the right track: after finding so many things I hated about Unreal, I still couldn’t leave it alone. I kept coming back. That kind of stubbornness usually means something.

I’ve opened Unity exactly twice since — once to make a backup, once for fun. Everything else has been Unreal.

Building the Console — Again

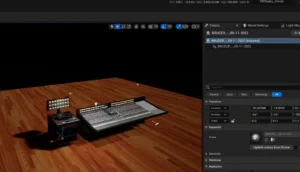

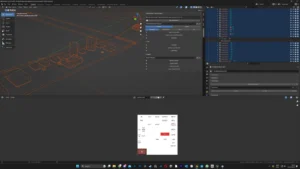

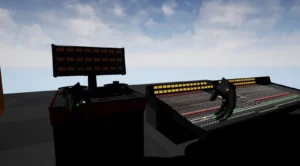

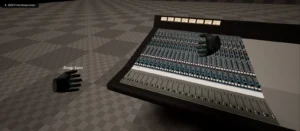

The first real test was recreating something meaningful. I modelled an SSL 4000 G-inspired mixing console in Blender — channel strips, faders, EQ sections, the works — imported it into Unreal, and started wiring up VR interaction and audio routing. I also built “the Bruder,” a Studer-inspired multitrack recorder, because what’s a vintage studio without tape machines?

Within about a month, I had a working demo: multiple audio tracks, volume control per channel, and the beginning of a proper mixing workflow. It wasn’t feature-complete, but it was functional — and it was fast. I was starting to genuinely prefer Blueprints over writing C# scripts, which surprised me more than anything.

The real jaw-drop moment: I was hitting 120 fps in Unreal without doing any optimization work. In Unity, maintaining decent frame rates in VR was a constant battle — every new feature meant another round of performance tuning. In Unreal, the renderer just handled it.

Why Unreal Wins

After several months of daily work in Unreal, here’s where it clearly comes out ahead for this project:

- MetaSounds — Handles about 95% of my audio needs out of the box. Node-based, real-time, and designed for exactly the kind of interactive audio work this project demands.

- Blueprints — Slower to build than C# scripts, but significantly more readable and reusable. I can look at a Blueprint I built weeks ago and immediately understand what it does. That wasn’t always true with my C# code.

- Rendering quality — The visual output is better out of the box than anything I achieved in Unity after careful optimization. Lighting, materials, post-processing — it all just looks right.

- Performance — 120 fps without trying. In Unity, that frame rate was a luxury I had to fight for on every scene.

- Debugging philosophy — Different approach than Unity, but once you adapt, the tools are solid. Blueprint debugging in particular is very visual and intuitive.

The Growing Pains

I want to be honest about the downsides, because there are plenty. Unreal is not a frictionless experience:

- The Outliner is genuinely terrible for complex scenes — finding and organizing actors is harder than it should be.

- Blueprint editor tooling feels incomplete in places. Basic quality-of-life features are missing.

- There are too many settings. Every panel has sub-panels with sub-panels. Finding the right toggle can take longer than solving the actual problem.

- The editor itself slows down noticeably on larger projects. Load times, compile times, general responsiveness — it all degrades.

- FBX import has persistent pivot point issues that require workarounds every time.

- Plugin conflicts are common and poorly communicated. Something breaks, and you’re left guessing which plugin caused it.

- The tutorials and documentation lag behind the engine. Official docs are sparse, and community resources vary wildly in quality.

- Android/Quest builds are painful. The pipeline is complicated, fragile, and poorly documented.

- VR integration is behind where Unity is. It works, but the tooling and templates aren’t as mature.

No Looking Back

Despite that list of complaints — and I could probably add more — I’m not going back. The things Unreal does well are exactly the things this project needs most: exceptional audio capabilities, beautiful rendering without constant optimization, and a visual scripting system that makes complex interactions manageable.

Eight years of Unity experience doesn’t disappear. A lot of the concepts transfer, and the pain of learning a new engine gets smaller every week. But the studio I’m building now already looks and sounds better than anything I achieved in Unity, and I’m only a few months in.

The Retro Recording Studio is being rebuilt from the ground up in Unreal Engine 5. It’s terrifying, it’s exciting, and it’s absolutely the right call.